The Variable Course Modality

What Is a Variable Course?

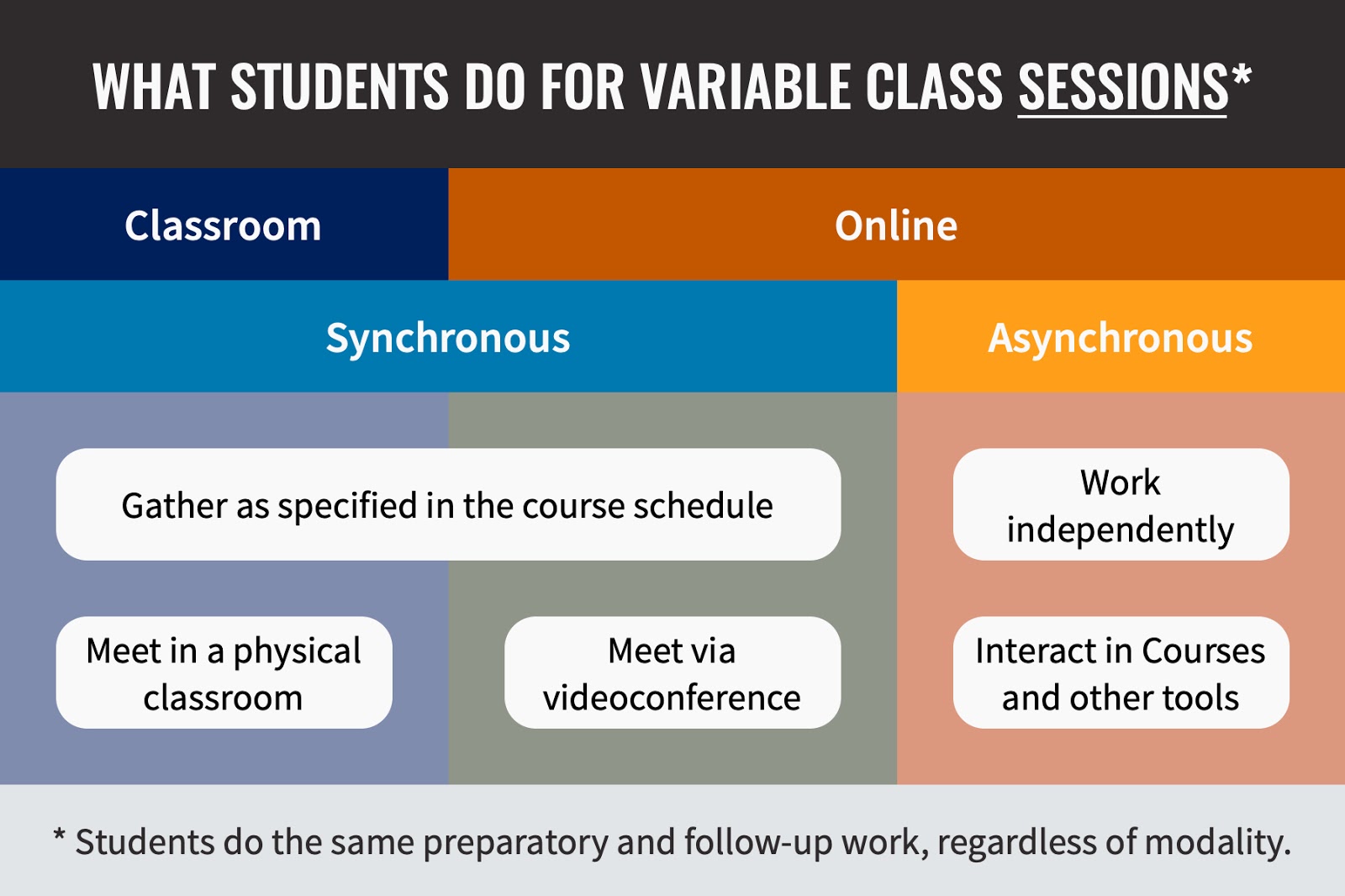

In response to the ongoing health risks posed by the COVID-19 pandemic, Seaver College empowered faculty to select the modalities for their own courses, course by course. All courses will receive a course tag indicating the venue: Classroom (C), Online (O), or Mixed (M). Courses may also receive the Variable (V) tag to indicate that students can participate in class sessions remotely, using some combination of synchronous videoconferencing and asynchronous activities. Online classes automatically carry the Variable tag; for Classroom and Mixed classes, individual faculty members choose whether to add the Variable tag.

Variable Courses and the Hyflex Model

Earlier versions of the Fall 2020 course modality labels used the term hyflex for a course that would be tagged as Mixed Variable (MV) using the final modality tags. The hyflex (hybrid-flexible) course model was pioneered at San Francisco State University in 2005 as an attempt to expand a program by incorporating online students into existing traditional on-campus courses.

Seaver's Variable courses differ from classic hyflex courses in three significant ways:

- In the original hyflex model, onsite classes were conducted in traditional formats, and online students participated asynchronously. In the fifteen years since hyflex debuted, the combination of ever-improving video compression and ever-wider access to high-speed internet has given us the option of synchronous participation in an onsite course by students who are physically remote from the classroom. Seaver College classrooms have received new technologies to support this kind of synchronous onsite-online integration.

- Classic hyflex was originally motivated by a desire to expand an existing program by adding online students, and since then has been adopted mostly by faculty who want to maximize student choice. Seaver College's introduction of the Variable course designation seeks primarily to serve students whose lives have been disrupted by the COVID-19 pandemic in ways that make it unreasonable to expect on-campus or even synchronous participation from those students. The use of Variable instead of Flexible indicates that these courses will consider student needs, not necessarily that they will support all student preferences.

- In a classic hyflex model, students choose day by day which modality they will use to participate in class sessions. In Seaver's Fall 2020 model, students make a one-time choice about whether they will attend physical classes or participate online. Students who register online cannot later decide they want to attend onsite classes, because the registration data will be used to allocate classroom space.

Teaching a Variable Course

To implement a robust Variable course, a teacher needs to plan "in triplicate," considering how students can participate in core learning activities whether they are present in the classroom, attending remotely, or neither. While the original vision of hyflex was oriented toward allowing students to decide how they wanted to participate, the COVID-19 pandemic has removed that element of choice for some students. Students who fall ill or have high risk of doing so must remain isolated for their own wellbeing, and international students may be unable to return to campus whether they wish to or not, due to travel restrictions. Thus all three modes of interaction will be important to consider in planning Variable courses.

Teaching a Variable course can be very rewarding, giving you a sense of satisfaction in serving students with a variety of needs. Offering a Variable class opens up the course to students who otherwise could not take it, due to logistical impediments. On the other hand, a Variable course requires careful and complex planning. If you would like additional conversation about whether Variable is a good fit for your course, please contact the CTE.

For Further Information

The following resources on the hyflex course model may be useful as you design your own Variable courses.

- Beatty, B. J. (2007, October). Hybrid classes with flexible participation options – If you build it, how will they come? [Conference presentation]. Association for Educational Communications and Technology Annual Convention, Anaheim, CA.

- Beatty, B. J. (Ed.) (2015). Hybrid-flexible course design. EdTech Books. Retrieved from https://edtechbooks.org/hyflex/

- EDUCAUSE. (2010). 7 things you should know about the hyflex course model. EDUCAUSE Learning Initiative.

- Kelly, K. (2020, May 7). COVID-19 planning for Fall 2020: A closer look at hybrid-flexible course design. Phil on Ed Tech (blog).